The Story of Sandakan’s Death Marches

- devanandpaul

- Sep 6, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 6, 2025

Sandakan Memorial Park in Sabah, Malaysia, is no ordinary site. The place, now serene, was once a World War II POW (prisoner of war) camp in North Borneo (present-day Sabah) where Australian and British soldiers were held by Japanese forces. Few survived—most perished in the camp or during the brutal Sandakan–Ranau ‘death marches’ through Bornean jungles.

On my recent trip to Borneo with friends Rajashekar and Latha, we visited the park, which houses an interpretive pavilion, where photographs, letters, and documents line the walls.

Moving through the exhibits felt less like reading history and more like hearing voices from that time. This blog is an attempt to take you along on my walk.

The Fall of Singapore and the Death Marches

In late 1941 and early 1942, amidst World War II, Japan’s rapid victories swept them into Southeast Asia, climaxing in Britain’s shocking surrender of Singapore on 15 February 1942. Over 130,000 Allied troops were captured, including 15,000 Australians.

By July, 1500 Australian POWs (grouped as B Force) were transported aboard the hell ship Ubi Maru from Singapore to Sandakan (North Borneo), forced to build a military airfield. Huts built to hold 300 men were crammed with 1500, leaving no room to breathe, no space to rest. In 1943, about 770 British POWs and 500 more Australian POWs arrived, raising the camp strength to 2500.

By early 1945, with Allied advances threatening Borneo, the Japanese ordered the prisoners on a 260-kilometre march from Sandakan to Ranau through swamps, rivers, and mountains. Between January and June, three such death marches left Sandakan. The prisoners, starving and burdened with heavy loads, were executed if they collapsed. Of 470 men on the first march, only six survived; the second killed hundreds more; the third left no survivors.

Those too weak to walk were abandoned in the camp, which, in May 1945, was burned down by the Japanese, leaving 300 men exposed to rain, starvation, and tropical diseases. Executions followed. And on 10 June, over 70 were disappeared—never seen again.

By the end of the war, nearly all 2500 prisoners had perished.

Local Resistance

The story of the Sandakan POWs is well known. Yet beneath it lies a quieter tale of local resistance. Under the Japanese occupation, even the smallest act of defiance brought death, not just to the individual but to their family. Still, resistance took root.

Chinese families, many tied to the Kuomintang (a major political party in China), built underground networks, passing food and information. Filipino guerrillas from the Sulu Archipelago reached across the sea, keeping hope alive. Ordinary townsfolk and indigenous families risked their lives to hide escapees, share information, or provide food, water, and medical aid to the starving and sick prisoners.

Ernesto Lagan, a local Filipino-Sabahan policeman, was one such person secretly helping the prisoners until he was caught and executed by the Kempeitai, imperial Japan’s feared military police, leaving behind his wife and three young children to carry the weight of his sacrifice.

Halima binte Binting carried a similar burden. Her husband, Matusup bin Gangau, had helped maintain a secret radio, smuggled supplies, and aided escape attempts until his execution in 1944. Halima was arrested and tortured for speaking with Captain Lionel Matthews, the Australian officer leading the resistance from inside the camp. Unlike many, she survived.

Two families, different in origin, yet bound by the same story of courage and loss.

But courage lived amidst betrayal. The Kempeitai were known for ruling with torture and fear. And some, desperate to shield their families from starvation or punishment, divulged names and secrets.

The Six Who Survived

Of thousands of Australian and British prisoners sent to Sandakan, only six Australians returned home alive: Keith Botterill, Nelson Short, Owen Campbell, Bill Moxham, Richard ‘Dick’ Braithwaite, and William ‘Bill’ Sticpewich.

Private Keith Botterill from New South Wales endured years of cruelty before escaping during the 1945 death march. Villagers sheltered him until the war ended.

Bill Sticpewich, the last to escape, fled Ranau after more than three years in captivity. Sheltered by villagers, he survived to testify in Tokyo, helping convict the guards responsible for the Sandakan horrors.

Private Nelson Short also slipped away during one of the death marches and survived in the jungle with the help of locals. He was rescued by the Allied troops on 24 August 1945 and later returned to Australia.

Gunner Owen Campbell of Queensland escaped during the second death march. He was hidden and fed by villagers until Australian commandos found him.

Bombardier Dick Braithwaite of Newcastle broke away near Batas, midway on the death march. Starving and hunted, he was saved by locals and later rescued by a US Navy patrol boat.

Inside the Interpretive Pavilion

Photographs inside the pavilion are stark reminders of war. One shows Owen Campbell on his return to the POW camp site decades later, sharing his story.

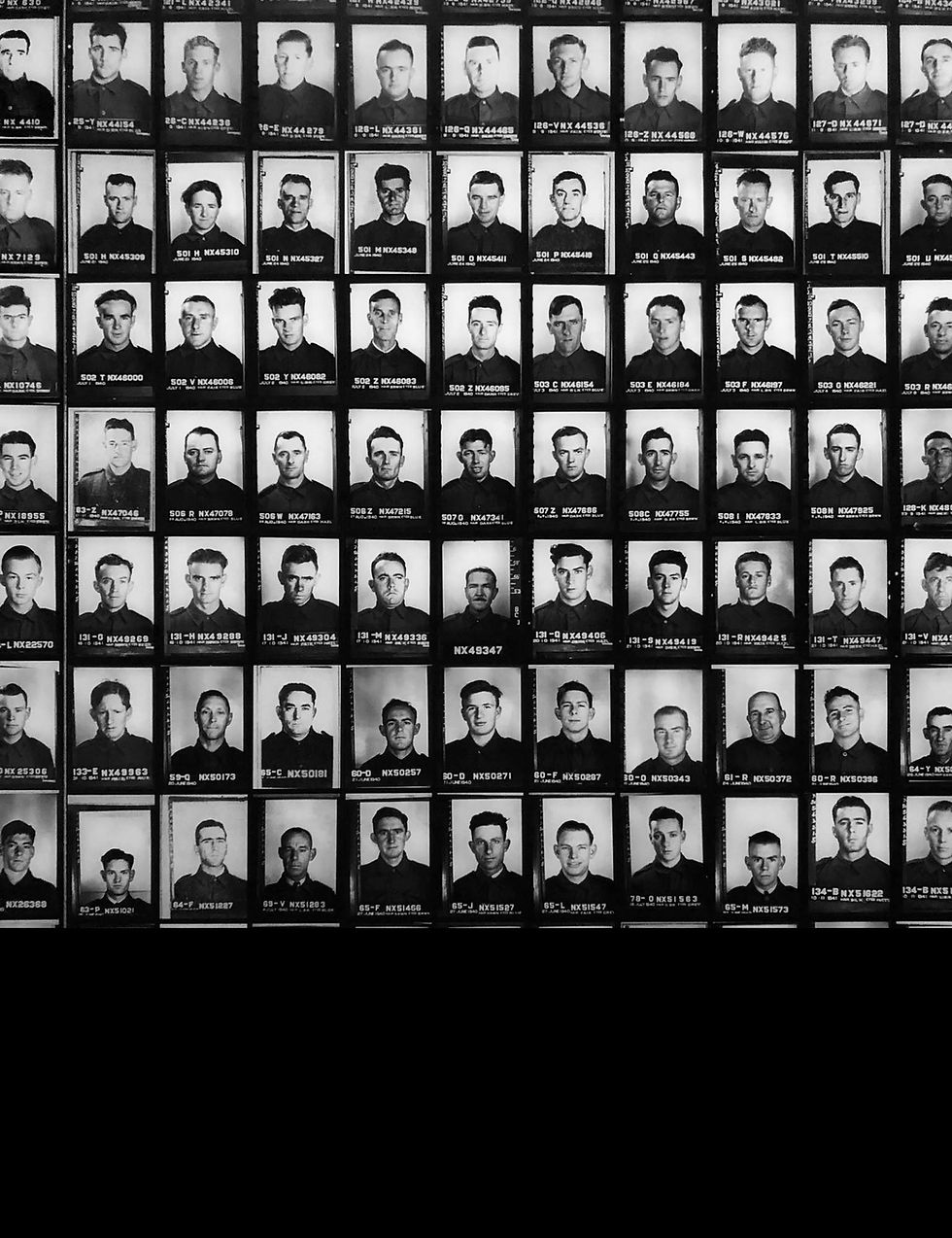

Faces of POWs who never returned home stare out from black-and-white images. Among them is Captain Lionel Mathews—a symbol of courage and sacrifice.

Also included are photographs of Dick Braithwaite, along with letters to his family during the war before his capture by the Japanese, and documents and notes related to his escape, interrogation, and tribunal testimony.

There is a roll of honour as well with the names of the dead. Exhibits also honour local villagers who risked everything to help the prisoners, and were later caught, tortured, and killed by the Japanese. A separate section details postwar investigations and trials of Japanese officers.

Crime and Punishment

After Japan’s surrender in August 1945, the Allied authorities sought to uncover the fate of POWs in North Borneo and discovered the rumours of Sandakan’s horrors to be tragically true—the camp was a graveyard.

The six survivors spoke of the starvation, forced marches, and executions, helping investigators piece together the full scale of the tragedy.

War crime trials opened at Labuan (an island off Borneo) on 3 January 1946. A total of 130 Japanese soldiers and officials were charged with crimes against the Allied POWs and civilians. Eight were sentenced to death by hanging; more than 50 received prison terms.

Walking the Pathway of the Sandakan Memorial Park

We wandered along the winding paths of the memorial park. At each turn we came across remnants of the old POW camp: a rusting excavator, sabotaged by the Australian POWs and left useless; an old steam generator, the main power source for the camp; farther on, a concrete water tank that belonged to the Japanese army kitchen; and finally, the eastern edge of the park—the camp’s main gate during the war, from where Mile 8 Road began, the road from where the three death marches to Ranau started.

The Sandakan Memorial Obelisk

At the heart of the Sandakan POW camp stood a great mengaris tree (one of the tallest tropical tree species), which was lost to fire after the war. In its place now stands the Sandakan Memorial obelisk. It is engraved with an inscription and floral motifs of Australia’s waratah, the United Kingdom’s English rose, and Malaysia’s hibiscus—symbols of a shared tragedy across nations.

Here, Anzac Day (Australian National Day) and Sandakan Day (15 August, honouring POWs and brave locals) services are held.

Echoes of Sandakan

Our greatest hope is that you will come home someday in good health, find a good job, marry some nice girl and settle down.

—Excerpt from a letter written to Aircraftman 2nd Class Alec Hughes by his uncle

Standing in the pavilion, reading these simple words, I felt their quiet hope echo across the park. Health, honest work, love, a settled life, all modest wishes—and yet, for the thousands who perished in Sandakan, even those humble dreams were denied.

They were not faceless victims, but sons, brothers, fathers, and friends—men with letters waiting to be answered, men who dreamed of ordinary happiness. To remember them is to promise never to forget, as a plaque from a Sandakan POW Memorial in Lismore (Australia) reminds us:

The towns and villages live on,

The Boys who played here once are gone.

The parrots cry, the river runs

And we do not forget our sons.

Lest we forget.

Related posts:

have read the story and I happened to know it before. Thank you for sharing it.

I have read some of the ww2 books and articles. Watched about 60 hours of videos about ww2. Most important book according to me is “the rise and fall of the third reich” by William shirer. When I first read the book long ago I was so shocked that I lost faith in humanity and I was even scared of myself because I asked myself whether I am also capable of descending into such inhuman nature under similar circumstances. And “The world at war” series of videos is a must watch. The Japanese outdid the nazis in brutalities committed especially in china you must…