Angkor Wat's Bas-Reliefs: Stories in Stone

- devanandpaul

- Jul 6, 2024

- 12 min read

Updated: May 10, 2025

Angkor Wat, the largest religious structure in the world and the main temple in the Angkor Archaeological Park, was constructed in the early 12th century by King Suryavarman II of the Khmer Empire. It is located about 8 km north of Siem Reap, Cambodia. In Khmer, angkor means capital city and wat means temple. The temple walls have high-quality bas-relief sculptures.

Angkor Wat was originally dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu, but many believe it was built as a funerary temple. Its westward alignment, symbolizing death, led scholars to conclude it was primarily a tomb. The anticlockwise direction of the bas-reliefs, common in Hindu funerary rites, supports this idea. However, Vishnu’s association with the west suggests Angkor Wat likely served as both a temple and a mausoleum for Suryavarman II.

In Hinduism, Brahma is the creator, Vishnu is the preserver, and Shiva is the destroyer and regenerator, forming the Hindu trinity. Angkor Wat, reflecting Vaishnavism (a major form of modern Hinduism), removes Brahma as the supreme god, placing Vishnu in his stead.

The temple complex spans over 160 hectares and features five towers—a central tower surrounded by four smaller towers—symbolizing the peaks of Mount Meru, the abode of the gods in Hindu mythology.

By the end of the 13th century, Angkor Wat transitioned to a Buddhist temple, which it remains to this day. After the 15th century, the site was largely abandoned because of the decline of the Khmer Empire; but it was never completely deserted, and continued to be an important spiritual site. Rediscovered by the Western world in the 19th century, Angkor Wat underwent several restoration efforts in the 20th century, which were disrupted by Cambodia’s political unrest in the 1970s and resumed in the mid-1980s with extensive repairs, including dismantling and rebuilding sections. And in 1992, Angkor Wat was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Today, it is a major pilgrimage site and tourist attraction, appearing even on the Cambodian flag.

In February 2024 my long-held dream of visiting Angkor Wat came true. As I stepped through the gates of the temple complex, a wave of disbelief washed over me. The grandeur of the ancient structures, the intricate carvings, and the serene beauty of the surrounding landscape exceeded all my expectations.

In this blog, I will take you on a tour of the main temple of Angkor Wat.

Tour of Angkor Wat Main Temple

Entrance and Outer Enclosure

The approach to Angkor Wat begins with an 800-feet-long sandstone causeway running across a moat surrounding the temple. This raised pathway is flanked by large naga balustrades. The nagas were believed to ward off evil spirits.

The moat is a 570-feet-wide rectangular water body that served to protect the temple. It is also thought to symbolically represent the oceans surrounding Mount Meru.

The causeway ends in a flight of stairs leading to a small cruciform terrace guarded by impressive statues of lions and nagas.

Ascending the stairs symbolizes the beginning of a sacred ascent of Mount Meru. From this point, you will continually ascend until reaching the temple’s third floor, at which point the five towers represent the five peaks of the mythical mountain. The towers gradually become visible as visitors cross the moat and enter the temple’s sacred grounds.

In ancient times, only high priests and the king likely had access beyond the first floor. Common people may have had access only to the bas-reliefs on the first floor.

Angkor Wat’s building materials

Khmer architects had mastered the use of sandstone as the primary building material, moving away from brick and laterite. Sandstone blocks make up most visible areas, and laterite has been used for the outer walls and concealed structures. The binding agent joining the blocks remains unidentified, although slaked lime or natural resins are possible candidates.

The sandstone blocks for the temple were quarried from Phnom Kulen, over 50 km (31 miles) away, and transported on rafts down the Siem Reap River. The construction involved 300,000 workers and 6000 elephants, according to inscriptions, but the temple was never completed.

There are two libraries on the temple grounds, one on either side of the central walkway. They likely held sacred texts and are examples of the sophisticated Khmer architecture.

Near the entrance are two large rectangular pools. During sunrise, the image of the temple towers is reflected in the water of the pools, creating a stunning view—a favourite among photographers.

First Level: Outer Gallery

The first level of the temple boasts on most of its surfaces (walls, columns, lintels, and roofs) bas-reliefs depicting scenes from Indian literature, such as unicorns, griffins, winged dragons, warriors, and celestial dancers. The gallery walls feature nearly 1200 square metres of extensive bas-reliefs, which likely took hundreds of craftsmen decades to complete. Some walls have holes in them, suggesting the walls were once decorated with bronze sheets, highly prized and often targeted by robbers.

Originally, most reliefs had Hindu themes, depicting Hindu myths, representations of Hindu heavens, and scenes of the king and his court, but later Khmer kings and Buddhist monks added Buddhist images. The gallery once housed thousands of free-standing statues as well; now only 26 remain.

More details on the bas-reliefs appear later in the blog. The interpretations of the reliefs are largely based on assumptions and speculations rather than concrete facts, due to the temple being abandoned for 400 years. Yet those who love mythology might find the stories interesting.

Second Level: Inner Gallery

The second-level gallery provides access to various parts of the temple. The outer wall of this gallery is unadorned, likely intended for meditation by priests and the king.

The inner walls have carvings of over 1500 apsaras (a class of celestial beings in Hindu and Buddhist cultures), offering visual and spiritual delight. Although these nymphs initially appear repetitive, closer inspection reveals uniqueness in their intricate hairstyles, headdresses, and jewellery; and they break from traditional temple decoration by standing in groups, linked arm in arm, and posing coquettishly. Unfortunately, many of these carvings have suffered damage from chemical exposure and bat droppings.

In this level, the doorways have lintels and pediments. Lintel is the large stone above the doorway. Pediment is an ogive-shaped structure above the lintel. It has carvings of mythological scenes and is framed by makaras (creatures with snake bodies and lion heads) with gaping mouths.

Third or Upper Level: Central Sanctuary

Twelve massive stairways (three on each side) lead to the third (and top) floor, though likely only the central western one was in regular use. The others mainly supported the third-floor towers, addressing structural weaknesses noticed a century earlier in Baphuon, a 11th-century temple in Angkor, which is now almost completely destroyed.

Each stairway leads to an entry tower, which in turn is connected to the central tower by passages with two rows of columns. Each entry tower has a porch and columns. Four such entry towers dominate the corners, and a narrow covered gallery with pillars, windows, and balusters runs around this level.

Central Tower: The central tower is the highest point of Angkor Wat, rising majestically 65 metres above the ground level, and is capped with a lotus-shaped top. This tower symbolizes the summit of Mount Meru.

Inner Sanctuary: The sanctuary, or sanctum, originally housed a statue of Vishnu, whom Angkor Wat was dedicated to. The sanctum is a serene space intended for worship and meditation. This sacred area, likely reserved for high priests and the king in ancient times, offers stunning views of the surrounding temple complex and the lush Cambodian landscape.

Walking around the gallery of the upper level, you can see the countryside, the causeway in the west, and the towers. The view, though not quite aerial, showcases the architects’ audacity in embarking upon such a grandiose plan.

The Bas-Reliefs of Angkor Wat

The bas-reliefs, which appear in the first level of the temple, are divided into eight sections, two per wall of the square gallery, each depicting a specific theme:

The temple of Angkor Wat attracts over 4 million visitors annually, but most overlook the detailed bas-relief sculptural panels in the first floor. This is primarily because they rush to the top floor, and few guides possess in-depth knowledge of these artworks. This blog aims to raise awareness about these bas-relief panels and highlight the brilliance of the unknown Khmer artists who crafted these masterpieces.

1. Churning of the ocean of milk (Samudra Manthana)

In Hinduism, the churning of the ocean of milk is an important event in the eternal struggle between gods (devas) and demons (asuras). Weakened by a curse from Durvasas (an irascible sage in Hindu mythology), the gods seek the demons’ help to retrieve the elixir of immortality, amrita, from the cosmic ocean. Mount Mandara, a symbol of the world axis, becomes the churning stick, anchored by Vishnu as Kurma, his tortoise avatar. And Vasuki, the mighty serpent king, volunteers to be the churning rope. The demons hold the head of Vasuki and the gods hold his tail. As they churn the ocean to extract the elixir, Vasuki’s mouth releases a deadly poison. Upon the gods’ prayers to save the world from the poison, Shiva swallows it, turning his throat blue. In the battle for possession, the gods gain the elixir, restoring their strength.

The Churning of the Ocean of Milk is Angkor Wat’s most renowned bas-relief scene. Adorning the southern part of the east gallery, this scene depicts 88 demons on the left and 92 gods on the right wearing crested helmets. Together, they churn the sea in search of the elixir of immortality.

In the centre of the scene stands Vishnu holding Vasuki, the serpent. Flanking Vishnu are the gods and the demons. Kurma, the tortoise, prevents Mount Mandara from sinking into the ocean. Above the mount, the figure of the god Indra emerges.

In the centre of this panel, Ravana, the demon king in the Hindu epic Ramayana, with his ten powerful arms stretched wide, holds aloft the head of Vasuki, the five-headed naga. Below, a diverse array of life thrives, from shimmering fish to ancient crocodiles. Above, apsara dancers grace the heavens with their ethereal beauty. The churning of the Ocean of Milk unfolds with majesty and mythical resonance.

In this bas-relief a monkey is depicted holding the tail of the serpent Vasuki. Scholars have long debated the identity of this monkey. Some propose he is Hanuman, a divine monkey in the Ramayana; others suggest he might be Sugriva, the king of the vanaras, in the Ramayana.

A bas-relief showing Brahma in the middle of the churning of the ocean scene, alongside the gods.

2. Battle of Kurukshetra

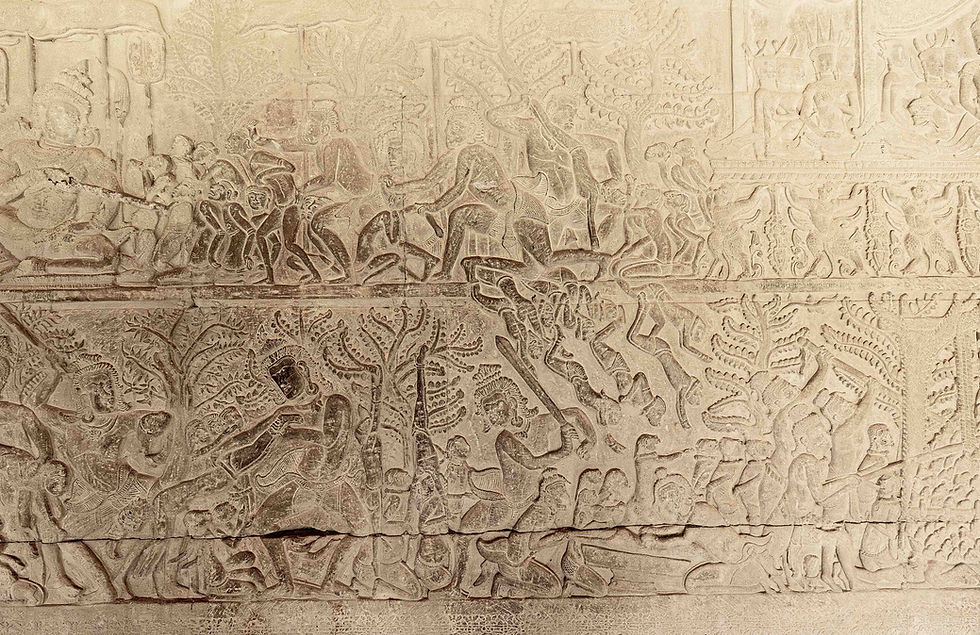

In the west gallery is the Battle of Kurukshetra (from the Hindu epic Mahabharata), one of the longest bas-reliefs in the world, spanning over 160 feet.

The battle scene portrays the dynastic war in Kurukshetra, India, between the princely cousin armies of the Kauravas and the Pandavas. Featured in this bas-relief are musicians, infantry, charioteers, and war elephants, marching from opposite ends and clashing in the centre, and dead soldiers. Headpieces distinguish the two armies.

Here, Bhisma, a major character of the Mahabharata and commander of the Kauravas, lies dying. His body is covered with countless arrows, creating a bed of sharp points.

At the centre of the bas-relief is Arjuna (a Pandava brother), identifiable by his charioteer Krishna, in his four-armed form, the incarnation of Vishnu.

The figure in this panel is Yudhishthira (the eldest Pandava brother), deeply devoted to morals and virtues (dharma). Son of Kunti, he was fathered by the god Yama because of King Pandu’s inability to have children.

Dronacharya, the archery teacher of the Kauravas and Pandavas, is depicted here as the only warrior fighting without a helmet.

In this relief, Karna (a main protagonist of Mahabharata) struggles to pull his chariot’s wheel out from the mud as his driver lies slain nearby.

Generally, the top of the sculpture panels portrays the great warriors (maharathis), commanders, or lead characters; the midsection features the lower-ranking generals; and the bottom depicts the foot soldiers.

3. Victory of Krishna over Banasura

Banasura is a thousand-armed demon king, whose daughter Usha falls in love with Krishna’s grandson Aniruddha. Using magic, she brings him to her palace. Seeing her, he falls in love with her, and they plan to elope. However, Banasura captures them and imprisons Aniruddha, forcing Krishna to go to war. A fierce battle ensues, in which he kills Banasura, and returns to Dwarka with Aniruddha and Usha.

The eight-armed Krishna is seen riding Garuda, his majestic eagle mount, in the battlefield.

Banasura in the heat of battle, his 1000 arms wielding various weapons, creating a dynamic and formidable image.

4. Suryavarman II’s Royal Procession

This sculptural panel is particularly unusual. It depicts the king not only with his queens and concubines but also with all his senior ministers and commanders, 21 names of whom are inscribed on the panel.

In his royal court, Suriyavarman II is sitting on a divan with serpentine-shaped legs, surrounded by parasols and attendants holding fly whisks.

Suriyavarman II’s battle procession against the Chams (indigenes of Vietnam)

Suriyavarman II at the centre of the royal army

5. Heavens and Hells

The bas-reliefs at Angkor Wat vividly depict the heavens (swargas) and hells (narakas), showcasing 37 heavens and 32 hells. The lower portion of the reliefs graphically illustrates the elaborate and gory punishments inflicted on sinners, emphasizing the consequences of their misdeeds in striking detail. In contrast, the heavens are depicted serenely, with less intensity and less intricate descriptions.

Yama, the lord of justice and death, sits authoritatively with Chitragupta on his left. Chitragupta keeps an account of each person’s actions during their lifetime. When a person dies, Chitragupta presents his records to Yama, who then determines whether the individual is sent to hell or heaven.

Yama, the 18-armed ruler of Hell, rides a buffalo, symbolizing his power. Each arm holds an instrument of justice or punishment.

Chitragupta is depicted checking the records of souls. The detailed carving captures Chitragupta’s focused expression as he evaluates each soul’s actions, highlighting his role as the divine accountant. Surrounding him are souls awaiting judgment, their faces reflecting anxiety and anticipation, emphasizing the critical moment.

Here, sinners are being whipped, pushed, and dragged towards judgment with threads stuck in their noses.

The sinners are shown being led to a trapdoor to Hell. They are surrounded by demons ready to ensure their descent into the depths of Hell.

This relief portrays the punishment of driving a thousand nails into the body of men and women, chained in an upright position. The nails protruding from all over their bodies graphically illustrate the torment the souls endure.

6. Battle between Gods and Demons

The sculpture panel Battle between Gods and Demons, located on the western half of the northern wall, depicts the fierce battle where demons, deprived of the elixir by the gods, rally under Bali’s (a demon king in Hindu mythology) leadership to fight back. The carving shows 21 gods combatting with the demons, capturing the intensity of the mythical conflict.

Vishnu rides over the battlefield on his mount (vahana) Garuda, shown with outstretched wings and fierce eyes.

Here, Vishnu is riding Makara, a mythical hybrid sea creature. With an elephant or deer head and a crocodile or fish body, Makara moves powerfully through the turbulent waters of the battlefield.

7. Battle of Lanka

The Battle of Lanka, depicted on the northern section of the west gallery, showcases the climactic final battle in the Ramayana. This bas-relief panel illustrates Rama (the prince of Ayodhya, hero of the Ramayana, and incarnation of Vishnu) and his army of monkeys (Vanara Sena) as they confront and defeat the demon king Ravana to rescue Rama’s wife, Sita. The intensity of the battle is vividly captured, with detailed representations of the fierce combatants, heroic deeds, and the chaos of war, all culminating in Rama’s triumph and Sita’s liberation.

Ravana stands out with his multiple heads and arms, wielding an array of weapons, embodying his power.

In the Ramayana, the monkeys fight using their hands, nails, and teeth. They wield sticks, stones, uprooted trees, boulders, and severed mountain tops as weapons, whereas Ravana’s army is well equipped with spears, maces, swords, and bows and arrows. Ravana’s well-armed warriors mercilessly attack the ill-equipped monkeys. This relief faithfully depicts this contrast.

Rama is being carried on the mighty shoulders of Hanuman. Towering and powerful, he strides confidently through the chaos of battle, providing Rama with a steady platform.

8. Victory of Vishnu over Narakasura

The Churning of the Ocean (Samudra manthana) produces many jewels, including a pair of earrings, which Indra, the king of gods, gifts to his mother Aditi. The demon king Naraka steals the earrings and hides them in Pragjyotisha, his kingdom. Krishna marches with his army to retrieve them. The city is guarded by nooses with razor-sharp edges, controlled by the demon Mura. Krishna kills Mura, Naraka’s aides, and, finally, Naraka himself with his sudarshan chakra and retrieves the earrings. He also frees 16,001 women held captive by Naraka on Maniparvata Mountain by uprooting the mountain, placing it on Garuda’s wings, and bringing it to Dwarka. To restore their dignity, he marries all the women. Then he goes to heaven and returns the earrings to Indra.

Final Thoughts

The visit to Angkor Wat was not just a sightseeing trip for me. Each stone tells stories of empires risen and fallen, of gods worshipped and forgotten. Wandering in the ancient corridors and towering spires, I felt deeply connected to the past, as if echoes of ancient prayers still lingered within the sacred walls. The intricate details etched on stone tell of a civilization that had once flourished here.

This blog captures just a fraction of the experience of visiting the main temple of Angkor Wat. To stand in the shadows of such a monumental architecture, to witness the dawn breaking over its majestic silhouette, is an experience words can scarcely capture. I hope it inspires you enough to explore this magnificent wonder and savour its timeless beauty.

Leave your queries in the comment box, or email me at: paul@endlessexplorer.in

I will be happy to answer them.

Related posts:

Having visited Angkor Wat myself just last year, I am still entranced by its sheer magnificence and historical richness. The article of Dev, "Angkor Wat's Bas-Reliefs: Stories in Stone" on Endless Explorer beautifully encapsulates the essence of this awe-inspiring monument, taking us all on a vivid journey through its intricate bas-reliefs.

The article brilliantly highlights the bas-reliefs that adorn Angkor Wat, particularly emphasizing the detailed representations of daily life among ancient Khmer citizens. These panels, etched with meticulous artistry, offer a window into a bygone era, vividly capturing scenes of bustling markets, courtly processions, and traditional ceremonies. They serve not just as historical artifacts but as vivid snapshots frozen in time, transporting visitors back to the glory days of the…

What an informative and visually stunning post! The bas-reliefs at Angkor Wat are truly a sight to behold, and this post does a wonderful job of explaining their historical and cultural significance. Thank you Dev Anand for sharing your insights and stunningly beautiful photos, it's made me want to visit Angkor Wat even more!

Greetings,

Hari

Enjoy! Udaipur

www.enjoyudaipur.com